Introduction

This project took place over the months of October and November in 2024. There were three main goals of the study. I tracked 41 days, but my sample size is 33 (n=33) as I identified and threw out 8 days that I deemed to be outliers.

1) The central goal of the experiment was to discover how two variables affected my overall mood. The first variable was the total number of hours worked, and the second variable was whether I worked a “late night,” defined as working after 8 PM.

2) A secondary goal of the experiment was to track what the overall complexion of my work as a graduate student looks like, to discover what the nature of my work was on the days with the highest mood rating. This would theoretically allow me to make informed decisions about how to optimize my success and wellbeing.

3) A tertiary goal was to discover the efficacy of self-tracking for someone such as myself, someone who is biased against quantified-selfing and believes that self-tracking ultimately brings about more harm than good.

My four hypotheses were as follows:

- The more hours I work in a day, the lower my mood will be.

- On days that I work after 8 PM, my mood will be lower.

- Discovering how I’m spending my time (projects/total hours/time of night) will increase the control I have over my life

- For a quantified-self skeptic, self-tracking will be beneficial for some things but will overall be a net negative for my life

Some relevant background information is that I am an English Literature master’s student at CU Boulder in the fall semester of the final year of my program. I am taking three graduate level classes, each of which are 3 credit hours. I work as a graduate assistant in the Center for Teaching and Learning and my contract calls for roughly 20 hours/week of labor. In addition to this, I am in the process of applying to PhD programs in information science.

Methodology

Tracking Time and Defining Work Allocation

The experiment was a self-tracking experiment with myself as the only participant. To track the total number of hours I worked, the time that I stopped working, and how much time I spent on each project, I used an app called Timing. Timing tracked everything on my Mac OS. It tracked what application I had open as well as queried the windows to see what I was doing within them. This was specifically relevant for Google Chrome, as it allowed me to properly classify between work and non-work related activities that I engaged with on my computer. As the user, I would retrospectively assign the work to the different “projects” I was managing. Moreover, the Timing app allowed me to manually input work completed apart from the computer, which I added times for each day. This work generally consisted of reading physical texts for my literature classes.

The eleven bins which I chose to create and allocate my time as work included the following: “Info 5871,” “Engl 5169,” “Engl 7019,” “GA Job,” “Personal Website,” “PhD Research and Application work,” “Salon Reading Group,” “Admin,” “Film Project,” “Tech and Mythology Conference work,” “Job Prospect work.”

The first three bins are my graduate classes. GA Job included everything for my on-campus job. “Film Project” ended up being insignificant as I spent less than 4 hours total on it over the course of the entire 40 days. “Salon Reading Group” is a personal obligation to a community of peers where we meet weekly to discuss assigned readings of historical content as we try to self-educate. “Admin” includes things that need to get done but don’t fit well into other tasks; these things included going through my email inbox, engaging in scholarship work, maintaining my to-do list, and scheduling. “Tech and Mythology Conference work” included preparatory work for a conference that I helped organize, as well as attending the actual conference itself. “Job Prospect work” included research into career pathways apart from my PhD and applications to alternative licensure teaching programs.

Mood

My goal in tracking my mood was to create a scale from -3 to 3 that only included integers and enter my mood daily into a spreadsheet before I went to bed. My mood was not an in the moment reading, but an estimated average of my mood throughout the entire day. On days when I did not have access to my laptop, I would make note of my mood with pen/paper and record it the following day.

In addition to the quantitative scale, my daily mood tracking included a column of short descriptions of what occurred in my day that I deemed to have the most impact on my mood. Here are some sample descriptions: “Finished essay, watched Megalopolis, hung with —- after,” “Climbing, smile 2 [movie in theater] with —-, productive work day,” “lethargic and head-achey, unproductive and anxious about future work.”

Results

Hypothesis 1: The more hours I work in a day, the lower my mood will be.

Figure 1: Scatterplot with the x-axis showing total number of daily hours worked and the y-axis showing the mood.

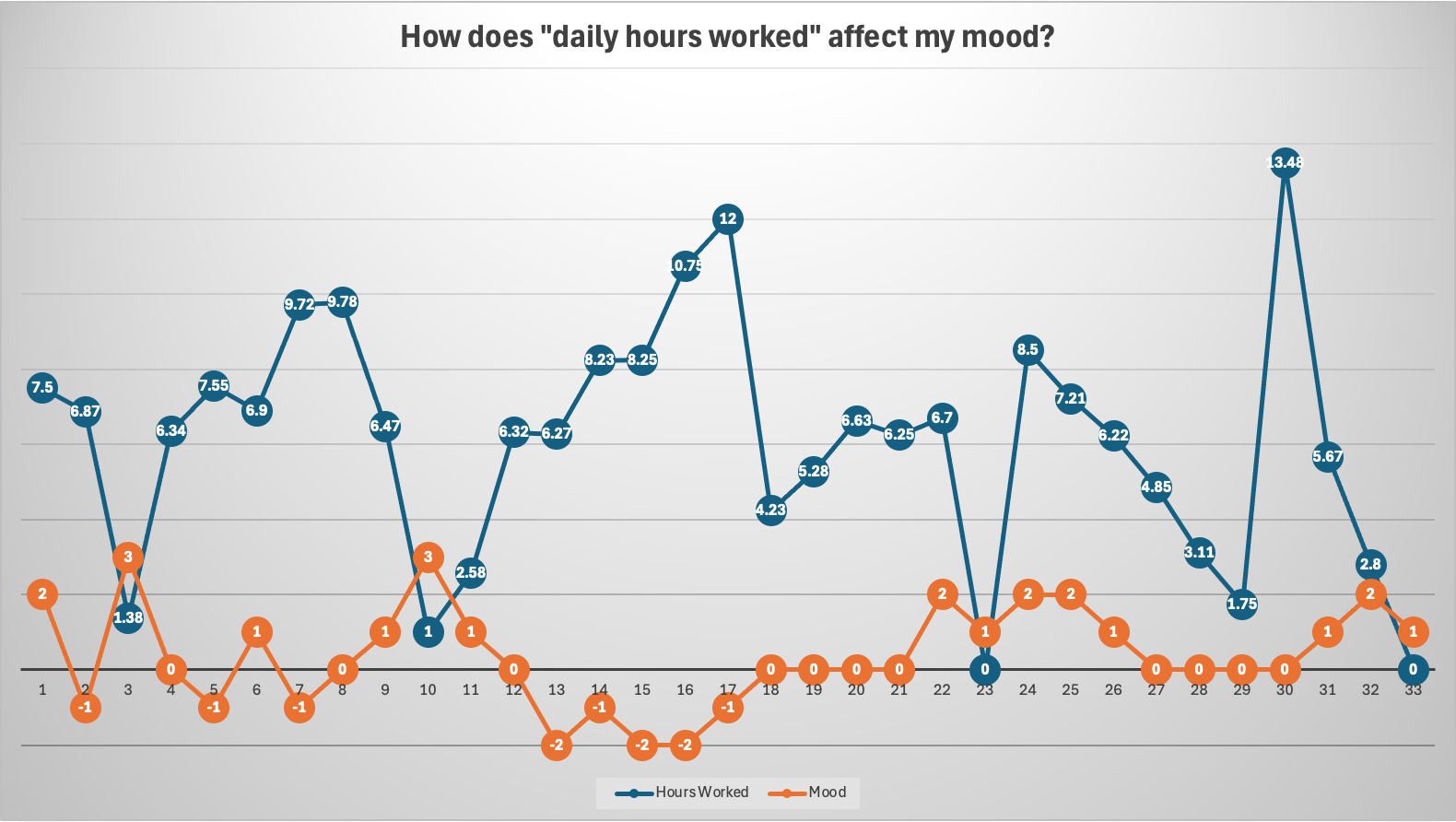

Figure 2: Line chart showing the inverse relationship between hours worked and mood. The blue line shows the total hours worked in a day and the orange line shows the mood for the day.

Figure 1 demonstrates that there is a moderate negative correlation of -0.48 between the total hours worked in a day and the mood score that corresponds with it, confirming hypothesis 1 to be generally true. For psychological studies, -0.48 is considered a strong correlation. For each additional hour of labor in the sample (n=33), my mood decreased by roughly -0.2.

Figure 2 reveals some interesting trends. Every day that I worked less than 3 hours, my mood was 1 or higher. And every occurrence of a mood score of 3 (n=2) I worked less than 2 hours. On days I worked over 9 hours (n=5), my mood never raised above 0.

Hypothesis 2: On days that I work after 8 PM, my mood will be lower.

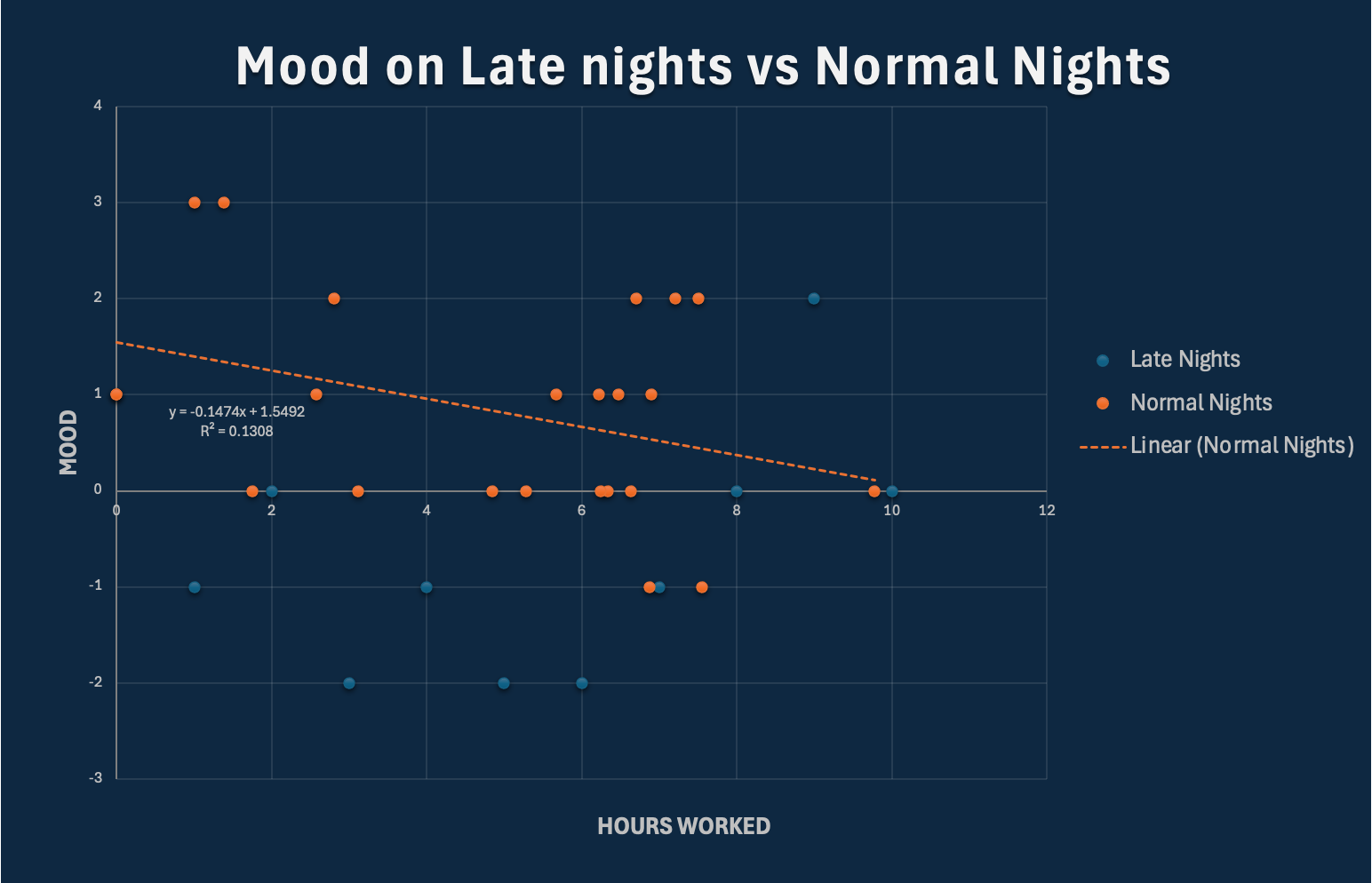

Figure 3: Mood on “late nights,” nights after 8 PM contrasted to mood on “normal nights,” nights before 8 PM.

Figure 3 charts my mood on late nights contrasted to my mood on normal nights. The average mood for nights when I worked after 8 PM (n=10) was -0.7 and the average mood for nights when I stopped work before 8 PM (n=23) was ~0.83. For nights that I worked after 8 PM, there was practically no correlation between the number of hours worked and my mood (-0.065), suggesting that the time of day I finish working may impact my overall mood more than the daily hours worked. For nights I ended work before 8 PM, there was a moderate negative correlation (-0.36) suggesting that the number of hours I worked in a day had a bigger impact on my mood on the days that I stopped working before 8 PM. Overall, there was a difference of 1.53 between “normal nights” and “late nights” which indicate that late nights are comparatively very bad for my mood.

Hypothesis 3: Discovering how I’m spending my time (projects/total hours/time of night) will increase the control I have over my life

Figure 4: Pie chart of total time spent on each project

Figure 4 demonstrates the proportion of time that I spend on each project. Visualizing the data in a pie chart enables me to see what I am spending the most amount of time on and try to proactively make adjustments to allocate my work time in a way that I believe to be more favorable for maintaining professional success while optimizing personal wellbeing. This chart reifies what I intuitively felt. It demonstrates my developed ability to prioritize the most challenging and pressing work that will benefit me as a graduate student while making sure that I continue to do things that are not as necessary for academic and career success, like my salon group. What I spent the most time on was my two favorite classes, then my job, then work for my PhD applications, then a required class that I do not enjoy very much.

Figure 4 also demonstrated to me that I have less control over my life than I would like. As a graduate student shouldering a heavy load, I am required to make sacrifices on things that I’d like to spend my time doing. Understanding what I am spending my working time on did not necessarily increase the control I have over my life, but it did confirm a story I already suspected. And it allowed me to reflect on whether my mood is high enough to rationalize the current path that I am on— and on nights that I am able to end work before 8 PM, I believe my mood to be satisfactorily high. Now the question is: can I figure out a way to ensure that I don’t work after 8 PM?

Hypothesis 4: For a quantified-self skeptic, self-tracking will be beneficial for some things but will overall be a net negative for my life

Hypothesis 4 cannot be easily defined as true or false. Overall, the experience of self-tracking with quantifiable data has made me aware of a few benefits. First and foremost, there are some insights that can be gleaned from quantitative data that are far harder to discover with qualitative data alone. A potential downside of this is that the quantified-selfer skeptic may lose confidence in their own intuition and gut feelings about things.

I do not feel as if I reached any extraordinary insights during this experiment, as I believe that before the experiment began, I was already highly self-reflective, employing qualitative forms of tracking like journaling and frequent introspection. The effort to track myself affected my perception of myself negatively. I became more concerned about extracting value, optimizing efficiency, mood, and success. In short, I feel like I became more like a computer and less like a human. My ideas of worth and value shifted to prioritize quantitative data, which I feel altered my personality in a way that is not favorable. I believe that it has made me a more serious person, which was not something that I was striving for.

The best part of self-tracking is seeing the data, analyzing it, and thinking about how I can make decisions to improve the quality of my life. The highly active form of data collection and constant quantitative reflection became tedious, which suggests that more passive forms of self-tracking may be ideal for those who have a negative view of quantified-selfing.

Discussion:

There are a few things that may have skewed the results of my data. The most obvious is the subjective nature of quantifying an average mood. Because I was the only participant in the study, I hope that the effects of the subjective scale are minimized. The second potential skew would be individual bias towards an expected outcome. Hypothesis 2 only came about because of proactive data analysis that revealed to me a trend. I decided to intentionally work several nights after 8 PM to increase the sample size, but the expected outcome of a lower mood score might have impacted the self-reported subjective mood score.

Another issue with measuring data such as these is with measuring work in “hours” because some hours are more productive than others. In a future study, it would be interesting to create a scale to measure productivity that contrasts hours worked pre and post 8 PM.

In another future study, it would be interesting to test how my mood is affected over time if my working weeks dip below a certain number hours of labor. During the time that I was tracking, I worked between 35 and 57 hours. I’d be curious to see the affect on my mood if I were to work less than 20 hours per week.

There were 8 days out of 41 that I decided to discard because of various reasons including struggles in my personal life, getting sick, and a federal election that produced a result that had a major effect on my mood for a few days.

Conclusion

In this study, I had three primary goals: 1) to determine how working hours/time of day affect my mood, 2) to discover what work made me the happiest and see if I could prioritize it, and 3) to test the efficacy of self-tracking for improving wellness in a self-tracking skeptic.

As far as goal 1 is concerned, I would label the experiment a success. I discovered a negative correlation between the total number of hours worked in a day and my mood. This suggested to me that, generally, the less hours a day I work the better my mood will be. Equally important was the realization that my average mood on late working nights was -1.53 lower in mood than on nights I stopped working before 8 PM, which equates to roughly 22%.

Goal 2 was not a clear cut success, in fact, I’d consider it more of a failure than a success. I discovered that on days when my mood was positive, it didn’t seem to correlate with any specific class or number of hours working. The qualitative notes were better at offering explanations as to why I was in a positive mood, and it usually corresponded with social events rather than the work that I was doing. Knowing what work I enjoyed most at any given time sort of just made me dread the work that I had to do that I was less excited about all the more.

When considering goal 3, I’m less sure about the qualitative results. I feel slightly more ambiguous about self-tracking than I did at the start of the experiment, but I don’t believe my feelings as a skeptic have changed all that much. I definitely formed a greater degree of respect for people who engage in active self-tracking, as it indicates a certain level of dedication and intentionality to engage with self-tracking as a practice. What comes with that level of dedication to quantified tracking, I fear, is a reduction of the complexities of what it means to be human. I worry that the trend to define oneself through quantified metrics–like step counts–can ultimately lead to counterproductive forms of identity construction.

Leave a comment