Exploring Cartophonic Mapping as a tool for Community Health

Images along the Map

Abstract

This project aims to explore cartophonic counter-mapping as a tool for undermining territorial logic and promoting community wellness between Indigenous, settler, and more-than-human populations. By creating a sonic map inspired by Indigenous sound art, I hope to subvert the rigid conception of boundaries, borders, and territories and encourage the idea that we are not separate from the land. Through localized knowledging, or the construction of community-based knowledge, I aim to take part in the process of employing decolonial imaginaries to improve overall well being for myself and my community. The results of the project suggest that the act of cartophonic map-making may be an effective tool for the map-maker in forming new understandings. Further studies are needed to determine if the cartophonic counter-map is effective for the map-receiver in deconstructing territorial logic. Even more studies are necessary to determine if cartophonic mapping is an effective tool for improving Indigenous-settler relations.

Introduction

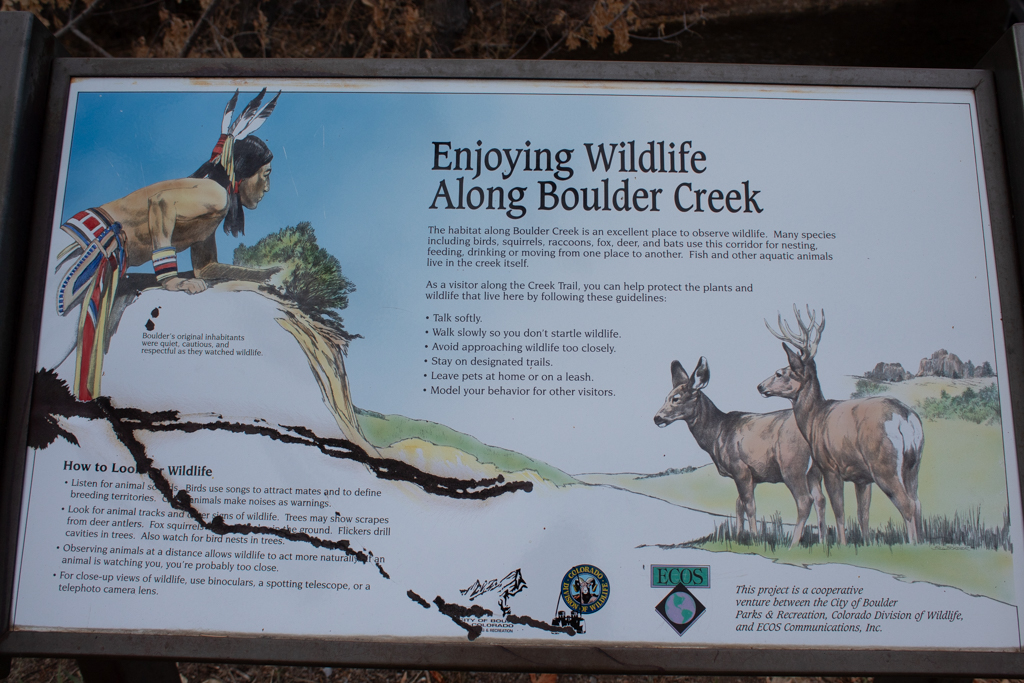

The goal of the project was to develop a cartophonic counter-map which “imagine[s] the potentials of sound art and the experience of listening to form new paradigms among Indigenous, settler, and more-than-human populations” (England, 2019). Through the act of creating a sound-map of the sights and sounds along Boulder Creek, I attempt to grapple with my own positionality as a settler, and recondition my spatio-temporal perception of the land and its original human and more-than-human inhabitants. My participation in the production of a counter-map aims to empower future decolonial imaginaries and to critique maps as a tool which enforce territorial logic. I hope to situate map-making as a participatory, fluid process which legitimizes the body as a sensing tool.

Through a transdisciplinary approach that involves the digital humanities, sound studies, Indigenous studies, geography, sociology, and information science, I examine the idea that maps are not merely historical artifacts, but active forms of technology which enforce certain perspectives–specifically that of the nation-state–on the land and its inhabitants. Through the creation of my own sonic map, paired with photography created in situ, I situate Boulder Creek as a multi-faceted, dendritic individual that sustains a wide variety of communities, both human and beyond. By de-centering territory in my map and centering the human body as a sensing apparatus, I aim to disempower ideas of the fixed nation-state with immovable borders and relationships. The goal of the map is to improve Indigenous-settler relations and promote overall community health and wellness within my local community of Boulder, Colorado.

It is of my belief that the map-maker (myself) experiences a more dramatic reconceptualization of their own spatio-temporal apparatus through the creation of the sonic-map, but it is my hope that the map-receiver will also experience some degree of change, both maker and receiver ultimately decentering territory and questioning their own relationality to the land and its inhabitants. Exploring new forms of mapping can help reimagine human beings as a part of the land, rather than removed from it. By letting the land and water speak in my map, rather than viewing it as a territory to exercise dominion over, we begin to restore critical ecological relationships.Finally, an important part of my methodological framework for counter-mapping as a form of community health is the realization that localized geographical prioritization is necessary for creating a shared identity and repairing relations between different types of people and the land in which we inhabit. Importantly, the map is embodied and relational, and is not placed on mathematical coordinates or satellite topographic imagery to be quantified for a broader public. If the map-receiver has a previous attachment to the sound and image represented in the map, then it will be more valuable to them. This differs from other forms of sound maps referenced in Thulin 2016 in that it does not just attach sounds to geographical land coordinates like the Cities and Memory project out of Oxford, UK. The process of creating an embodied map for a specific locality—localized knowledging, or the construction of one’s own local knowledge—creates a stronger bond for those within a defined locality.

Theoretical Underpinning

At the core of this project, there exists several theoretical underpinnings that guide my work. Rooted in sound studies and geography, I considered the merits of different phonographic techniques for mapping (Gallagher and Prior, 2014). Rooted in information science, I consider the dyadic characteristics of social networks (Heaney and Israel, 2008). Finally, rooted in sound and Indigenous studies, I consider the works of indigenous sound art as a basis to perform a mimetic form of mapping (England, 2019).

In their paper entitled “Sonic Geographies: Exploring Phonographic Methods,” Gallagher and Prior argue that phonography represents an underutilized methodology in the field of geography and that “audio recording produces distinctive forms of data and modes of engaging with spaces, places and environments which can function in different (and complementary) ways to more commonly used media such as written text, numbers, and images” (Gallagher and Prior, 2013).

Gallagher and Prior offer three filters —the term “filter” is used over the more common “framework” to deplatform the visual domain — for which to categorize phonographic material. The filters include 1) capture and reproduction, 2) representation, and 3) performance. Capture and reproduction is the most dominant and present filter, frequently used by sound engineers. It is about the reconstruction of a temporal moment utilizing hi-fidelity recordings (275). Representation is more ethnographic in nature, with the intent of contextualizing the sound and creating a soundscape that doesn’t exclude noise, which is largely defined as unwanted sound (276). The third filter, performance, involves “capturing traces” and organizing them into a “score for further playback” (277). It is more concerned with capturing affective forms of life. With my own cartophonic image map, I engage with all three filters.

In a chapter published in “Health behavior and health education: theory, research, and practice”, Heaney and Israel identify reciprocity and social support as important dyadic characteristics for mental health. Moreover, they found that geographical proximity helped in the formation of “social identity and the exchange of affective support” (Heaney and Israel, 2008). With reciprocity and social support as guiding virtues, I attempt to conceptualize a way to implement Boulder Creek as a unifying geological feature, or the focal individual, that can help form a common social identity involving a connection to the water that sustains all of us, and produce an increase in affective support for all of the life that relies on its waters.

Finally, I hope to apply a sound-based methodology that situates the settler-as-listener as described by Sara Nicole England. The settler-as-listener framework “articulates an ethics and politics to sound that may invite alternative discourses in the context of reconciliation” (England, 11). Importantly, England emphasizes the aesthetics of attentiveness that can be found within Indigenous sound art. It is with this attentiveness that I attempted to listen to the sights and sounds of the land when selecting what to record.

Related Work

In Postcommodity’s 2021 project Going to Water, the group utilizes sound and video of Owens Valley to demonstrate the ecological disaster experienced by the land and Paiute tribes due to the diversion of water from the valley via aqueduct to provide water for the city of Los Angeles, California. Chacon’s work is a form of counter-mapping that directly demonstrates the harm done on Indigenous communities of people and the land. The goal of my counter-mapping project is to imagine future forms of healing and community health through reparative relationships, beginning with the settler-as-listener methodology presented by England.

In the Cities as Memories Project founded by Stuart Fowkes, sound artists and engineers record sounds and then attach them to a satellite map with coordinates. Artists are tasked with the assignment of remixing the sounds to engage in a “sonic reimagining” (from the about the project page of their website) which depicts their own affective responses to the soundscape and their experience of it. In other words, artists engage in an act of performance, Gallagher and Prior’s third filter. This project serves less as a counter-map as it does not subvert mapping expectations as much as it adds sound to a normative mapping approach.

In Prost et al. (2023), HCI researchers concerned with Place-based Data Collection designed and tested the WalkYourWords map which explored ways to incorporate participatory design within communities. The app prioritized emotional affect and memory, utilizing images, video, and audio to create a map generated from community content. My sonic map places community health and connectivity above individual memory and rather than provide an app or a template, I call for others to explore their own types of counter-maps which explore their own relationships with the land and their own territorial logic.

Methodology

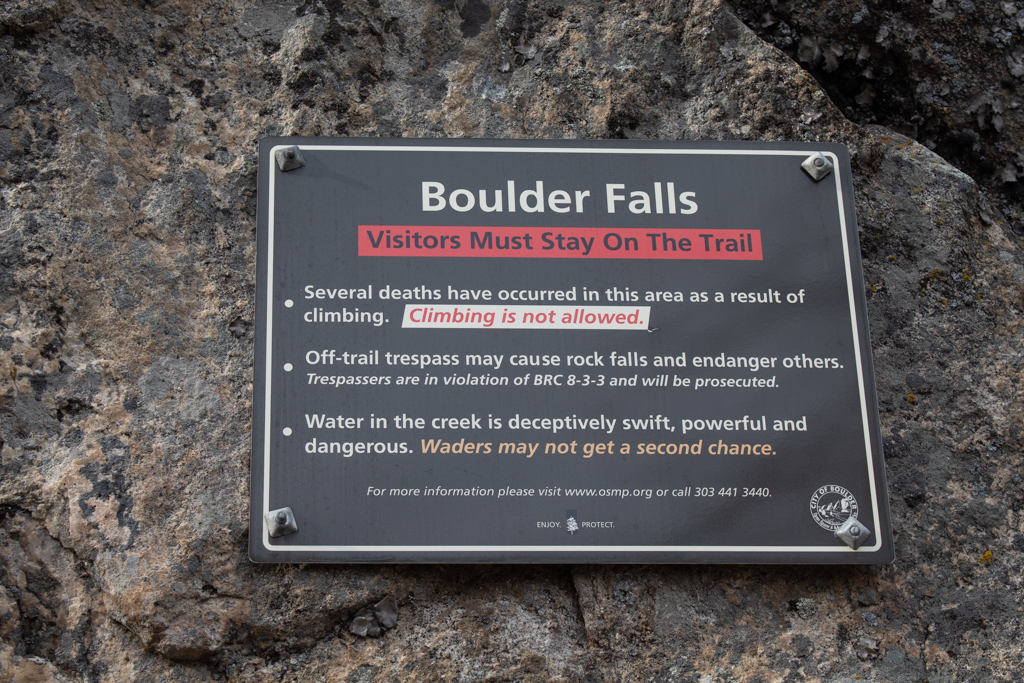

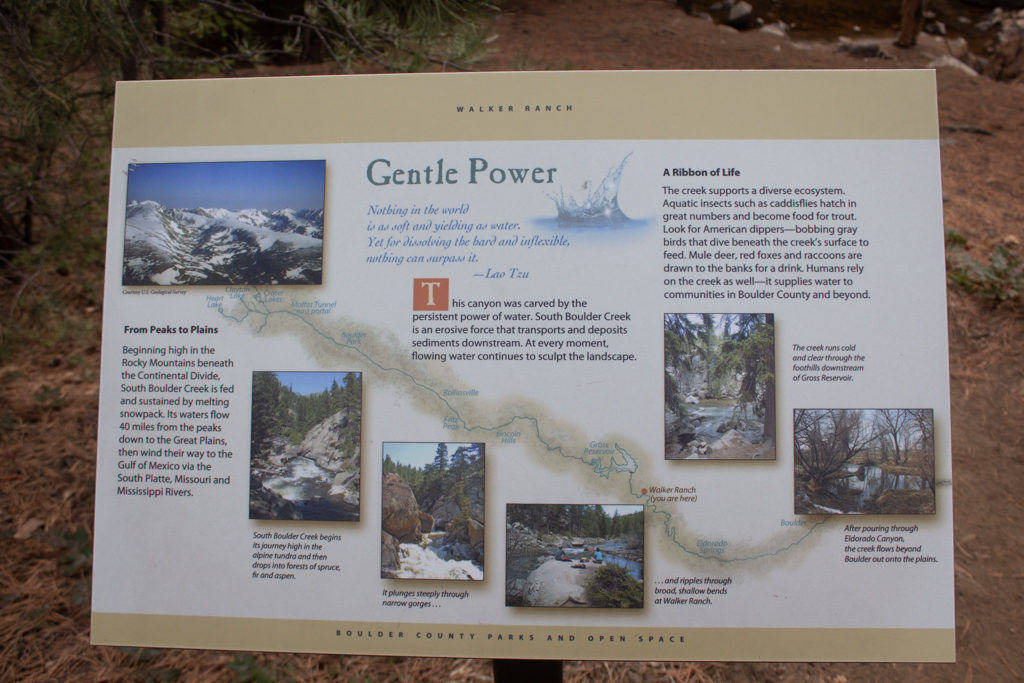

There were two parts to this project. The first was the recording of sound and image along Boulder Creek, and the second was the act of turning sound and image into a cartophonic video map. Recorded and photographed at different times of day and the year, the sounds in my map generally follow Boulder Creek, starting with its smaller inflowing streams that eventually flow together to form Boulder Creek. Middle Boulder Creek is paired aurally with South Boulder Creek as they flow west to east. Middle Boulder Creek links with North Boulder Creek at Boulder Falls, where it first receives the label of “Boulder Creek.” Boulder Creek links with South Boulder Creek much farther east, after the water travels separately through the township of Boulder, Colorado. Boulder Creek continues to flow East until it connects with the Platte River.

Through the process of recording sounds and photographs, I immediately realized the limitations of Gallagher and Prior’s first described filter of capture and reproduction. Hi-fidelity audio recordings that seek to capture “sound” and eliminate “noise” tend to pretend the recorder is not present. Two issues arise from this logic. The first being the recorder’s own selective bias of what sounds and images are important to record. In the field, I was forced to confront questions of where to go, and what sounds I should record. Are crows cawing more or less important than the sound of an American flag waving in the wind? The second problem with this filter is the assumption that the recorder’s presence does not in some way alter or affect the sound space they occupy. One such example of this is that as I was recording by Barker Reservoir, a dog walked over to me and started growling.

Gallagher and Prior’s second filter, representation, seeks to include all types of sound and does not differentiate between sound and noise. While I believe my cartophonic image map does include forms of this filter, I believe my map most represents the third filter, performance.

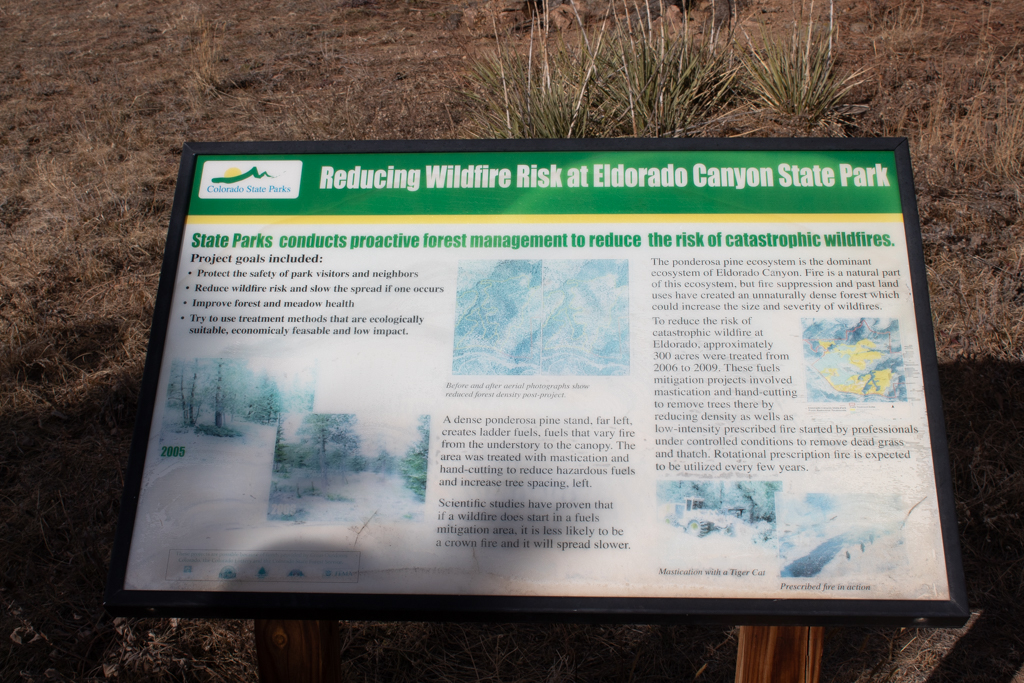

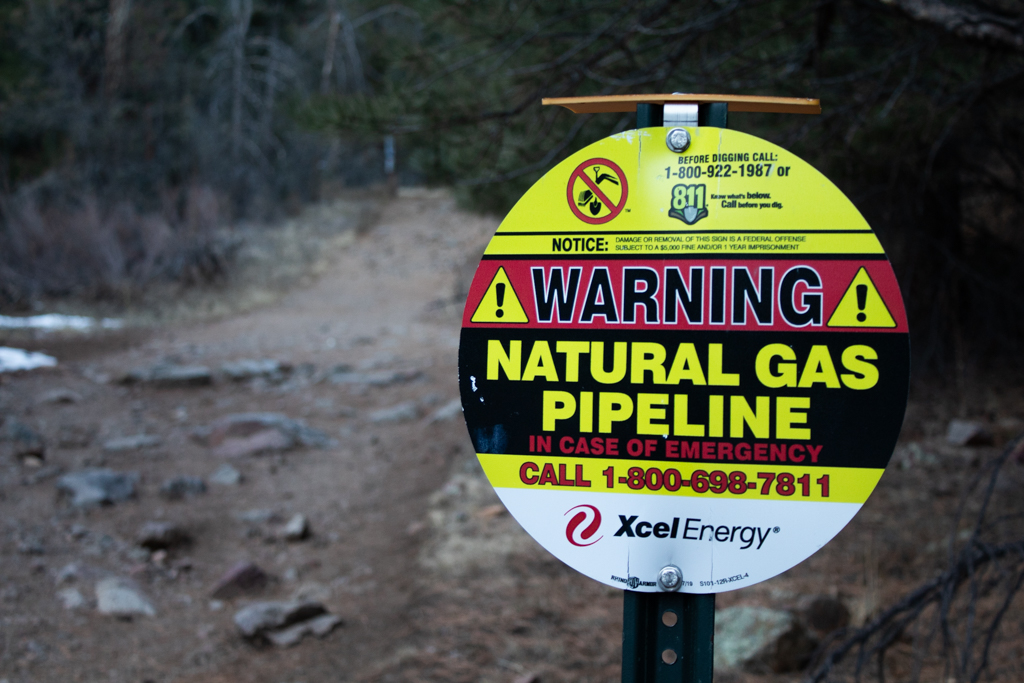

The second part of the project was making the map. The construction of the map engaged deeply with the third phonographic filter of performance: I recorded “traces” of locations and rendered them in an audio-visual score intended to produce a relational component to the land. By juxtaposing images created at different locations in a triptych format, I am able to more deeply communicate my own experience of listening to the land and demonstrate the narrative that I heard emerge from the land. Signs establishing territorial rules, themes of dispossession and ownership seemed particularly prevalent and necessary to include.

Findings

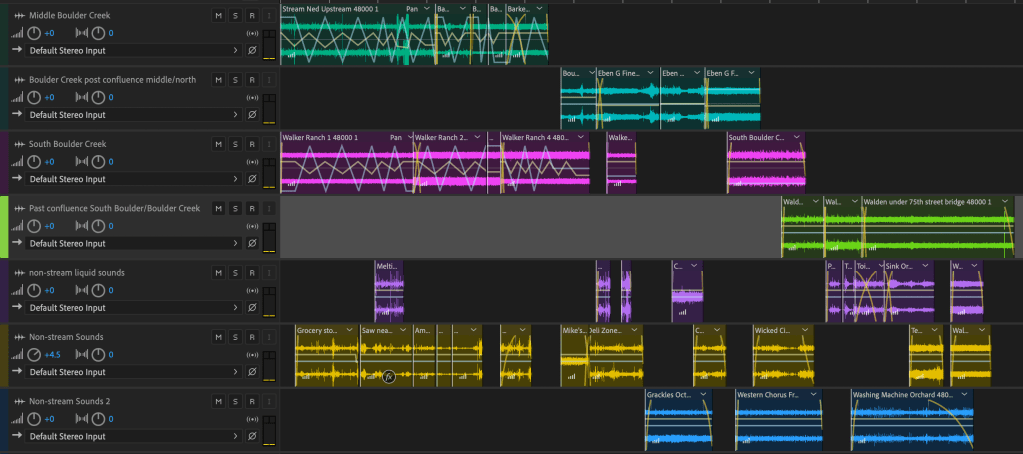

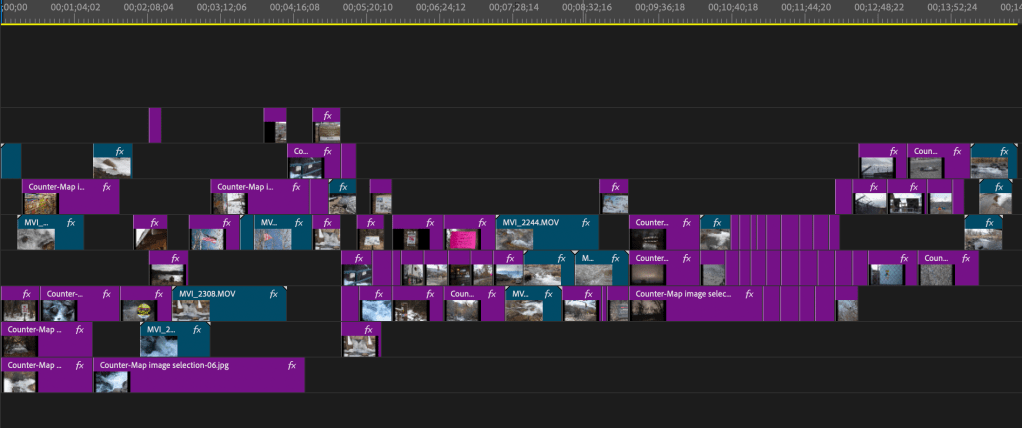

Figure 1: Screenshot from the video of my cartophonic image map

Map Representation

Through the inclusion of the sound score and the synchronous playing of sounds recorded at numerous locations along the creek, the map seeks not to represent a single location and a single point of time, but a spatio-temporal imaginary for the creek as images and sounds from different locations occur in order of the stream’s directional flow. By including the sound sequence from Adobe Auditions, I engage in a type of mapping where the sound waves and lines on the audio files create a visual representation of the sounds alongside Boulder creek. The panning and volume lines serve as the lines that I have drawn on my own sound map to establish relationality between the numerous inflowing streams before they eventually join together to form Boulder Creek. The images create a still representation of sound for the map-receiver to assign spatiality to. The link to the full video can be found in the Appendix.

Specific Representation

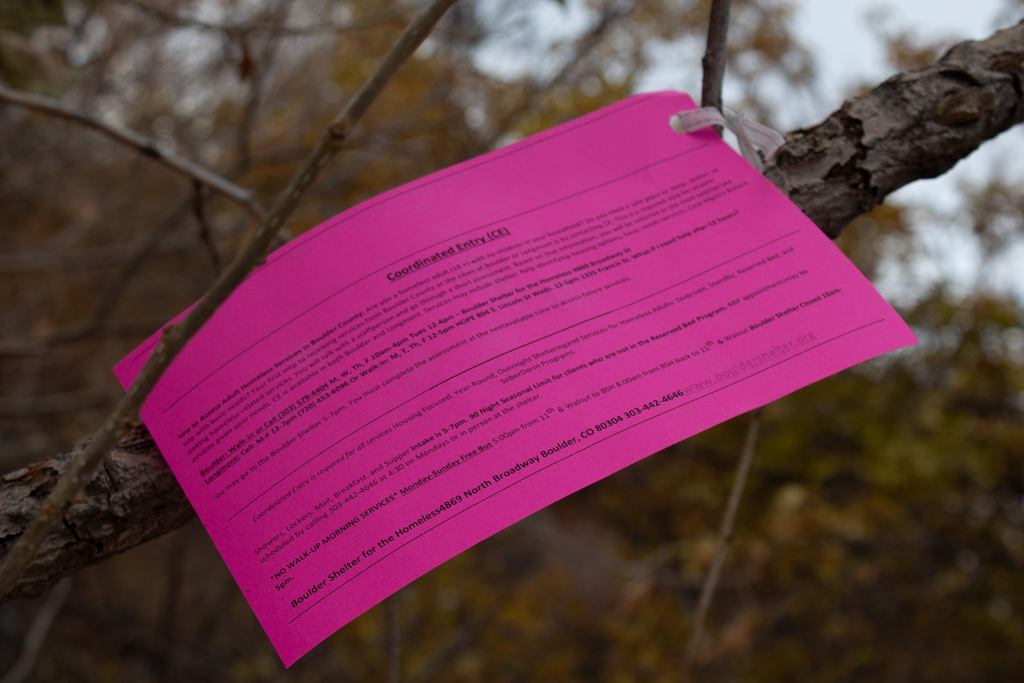

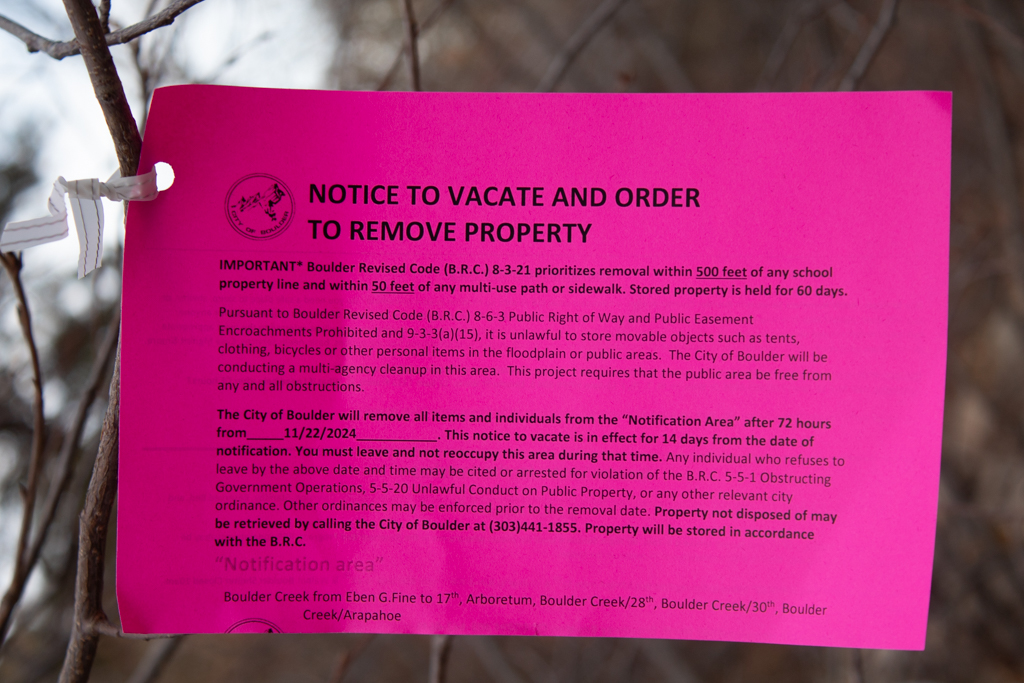

By placing images like the one found in Figure 2, a “notice to vacate” flyer targeted at a houseless community living along Boulder Creek, next to images like Figure 3 and 4, I call into question the territorial aggression granted by legislative bodies which allows for the continued dispossession of land occurring at sites along the stream.

Figure 2: “Notice to Vacate” flyer at Eben G Fine park

Figure 3: American flag near Barker Reservoir in Nederland, CO

Figure 4: Private property gate on the Walker Ranch Loop

By placing images like Figure 5 in conversation with Figure 6 and 7, I reflect on the ways that human interference with the stream can both harm and help non-human populations. Ironically, the Bald Eagle serves as a symbol of American freedom while at the same time embodying America’s territorial tendencies. Whether or not we should treat the Eagle as a symbol or respect it for a living organism with its own umwelt is up for debate.

Figure 5: Water treatment plant by Boulder Creek

Figure 6: Dead swallow by Water treatment plant

Figure 7: Living Bald Eagle by Boulder Creek water treatment plant

Figure 8: Graffiti of a Bald Eagle by Boulder Creek water treatment plant

Conclusion

Cartophonic Counter-mapping proved to be an effective tool for me to critically engage with and redefine my own relationality to the land. When placing sounds of South Boulder Creek from this year with recorded sounds from last winter, I felt my sense of linear time become more cyclical. I imagined the water as the same water as last year. Water that I carried in my body at one point before it found its way up into the sky, as snow in the mountains, and eventually back in that very same stream. It doesn’t matter if it is the exact molecules of hydrogen dioxide; what matters is the sense of connectedness derived from this experience of sonic map making.

Visual symbols–like signs with written language–and fences seem to provide a rigidity to the landscape that reinforce territorial logic and coloniality, whereas audio symbols seem to prove far more fluid and changing. This threatened my own territorial logic of immovable borders and boundaries and reaffirmed the importance and legitimacy of the sonic map as a tool for decolonial imaginaries which seek to repair and form new relationships between settlers as native inhabitants. It is unclear if cartophonic counter-mapping has as much of an impact on the map-receiver as it does the map-maker.

Acknowledgements

I’d like to thank Pilar Muñoz, Jane Forman, and Dr. Cheryl Higashida for the conversation and theoretical help on my project. Without them, I would not have been able to engage with the topics in anywhere near as thorough a way. Additionally, I’d like to thank Jake Fakult and Gabrielle Eastwood for accompanying me on two separate recording sessions. Your patience is greatly appreciated.

References

- Catherine Heaney and Barbara Israel. 2008. Social Networks and Social Support. Health behavior and health education: Theory, research, and practice (Fourth edition.). 189-210. Jossey-Bass. San Francisco, CA, USA.

- Manuela Boatcă. 2021. Counter-Mapping as Method: Locating and Relating the (Semi-)Peripheral Self. Historical Social Research / Historische Sozialforschung, vol. 46, no. 2, 2021, 244–63. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/27032980. Accessed 13 Dec. 2024.

- Michael Gallagher and Jonathan Prior. 2014. Sonic geographies: Exploring phonographic methods. Progress in Human Geography, 38(2), 267-284. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132513481014

- Postcommodity. 2021. https://www.postcommodity.com/GoingToWater.html

- Samuel Thulin. 2016. Sound Maps Matter: Expanding Cartophony. Social & Cultural Geography 19 (2): 192–210. doi:10.1080/14649365.2016.1266028.

- Sara Nicole England. 2019. Lines, Waves, Contours: (Re)Mapping and Recording Space in Indigenous Sound Art. Public Art Dialogue 9 (1): 8–30. doi:10.1080/21502552.2019.1571819.

- Sebastian Prost, Vasilis Ntouros, Gavin Wood, Henry Collingham, Nick Taylor, Clara Crivellaro, Jon Rogers, and John Vines. 2023. Walking and Talking: Place-based Data Collection and Mapping for Participatory Design with Communities. In Designing Interactive Systems Conference (DIS ’23), July 10–14, 2023, Pittsburgh, PA, USA. ACM, New York, NY, USA, 16 pages. https://doi.org/10.1145/3563657.3596054

- Stuart Fowkes. 2015. https://citiesandmemory.com/sound-map/

Leave a comment